Capital punishment in the United States

| Part of a series on |

| Capital punishment |

|---|

| Issues |

| Debate · Religion and capital punishment · Wrongful execution |

| Current use |

| Belarus · PR China · Ecuador · Egypt · India · Iran · Iraq · Israel · Japan · Malaysia · Mongolia · North Korea · Pakistan · Russia · Saudi Arabia · Singapore · South Korea · Taiwan (ROC) · Tonga · United States |

| Past use |

| Australia · Brazil · Bulgaria · Canada · Denmark · France · Germany · Italy · Mexico · Netherlands · New Zealand · Philippines · Poland · Portugal · Romania · San Marino · Turkey · United Kingdom · Venezuela |

| Current methods |

| Decapitation · Electrocution · Firing squad · Gas chamber · Hanging · Lethal injection · Shooting · Stoning · Nitrogen asphyxiation (proposed) |

| Past methods |

| Boiling · Breaking wheel · Burning · Crucifixion · Crushing · Disembowelment · Dismemberment · Execution by elephant · Flaying · Impaling · Necklacing · Sawing · Slow slicing · Torture |

| Other related topics |

| Crime · Death row · Last meal · Penology |

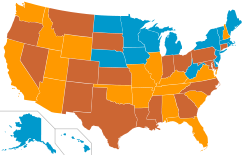

Color key: No current death penalty statute Statute or method declared unconstitutional Not applied since 1976 Has performed execution since 1976

Capital punishment in the United States varies by jurisdiction. In practice it applies only for aggravated murder and more rarely for felony murder or contract killing.[1] Capital punishment existed in the colonies that predated the United States and that were later annexed to the United States under the laws of their mother countries and continued to have effect in the states and territories they became.

The methods of execution and the crimes subject to the penalty vary by jurisdiction and have varied widely throughout time. Some jurisdictions have banned it, others have suspended its use, but others are trying to expand its applicability. There were 37 executions in 2008.[2] That is the lowest number since 1994[3] (largely due to lethal injection litigation).[4][5] There were 52 executions in the United States in 2009, 51 by lethal injection and 1 by electric chair (Virginia). Texas executed the largest number, 24, followed by Alabama with 6; Ohio 5; Virginia, Oklahoma, and Georgia 3; Florida, South Carolina and Tennessee 2; and Missouri and Indiana 1.[6]

Controversy

Capital punishment is a controversial issue, with many prominent organizations and individuals participating in the debate. The United States is one of only three industrialized democracies that still have it. The others, Japan and South Korea, both have de-facto moratoria in effect. In July 2010, Japan interrupted its de-facto moratorium by executing two prisoners, but Justice Minister Keiko Chiba, who opposes the death penalty, wants to review the death penalty.

Arguments for and against capital punishment are based on moral, practical, and religious grounds. Advocates of the death penalty argue that it deters crime, is a good tool for prosecutors (in plea bargaining for example),[7] improves the community by making sure that convicted criminals do not offend again, provides closure to surviving victims or loved ones, and is a just penalty for their crime. Opponents argue that the death penalty is not an effective means of deterring crime, is unnecessarily barbaric in nature, is levied disproportionately upon men and racial minorities, cheapens human life and puts a government on the same base moral level as those criminals involved in murder.[8]

Another argument (specific to the United States) on the capital punishment debate is the cost. The convict is more likely to use the whole appeals process if the jury issues a death sentence than if it issues life without parole.[9] But others who contest this argument say that the greater cost of appeals where the prosecution does seek the death penalty is offset by the savings from avoiding trial altogether in cases where the defendant pleads guilty to avoid the death penalty.[10]

Historically, several states have been without capital punishment - the earliest being Michigan, which has not carried out a single execution of its own since it entered the Union (one federal execution occurred in Michigan in 1938), and shortly after attaining statehood abolished the death penalty for ordinary crimes, making it the first English-speaking government in the world to do so. Other states long without the death penalty are Wisconsin (with the distinction of being the only state to perform a single state-level execution in its history), Oregon (though only temporarily), Rhode Island (although later reintroduced, it was unused and abolished again), South Dakota (though only temporarily), Maine, Washington (though later abolished three times, one time by the Supreme Court's decision in Furman v. Georgia, it was reintroduced and remains in use), North Dakota, Minnesota, West Virginia, Iowa, Vermont and the District of Columbia. Two states - the newest, Alaska and Hawaii - abolished the death penalty prior to statehood (in Alaska, some extrajudicial killings took place after statehood).[11] One state, Oregon, abolished the death penalty through an overwhelming majority in a 1964 public referendum,[12] but reinstated it in a 1984 joint death penalty/life imprisonment referendum by an even higher margin, after a similar 1978 referendum succeeded but was not implemented due to judicial rulings.

In the so-called "modern era of capital punishment", two states have legislatively abolished the death penalty and two have de facto abolishment through their state judiciaries. In 2007, New Jersey became the first state to repeal the death penalty in the modern system of capital punishment,[13] and New Mexico followed in 2009 (though not retroactively, and with some advocating reinstatement).[14][15] But in states with a large death row population and regular executions, including California and Texas, the death penalty remains strongly in the landscape and is unlikely to end at any time soon.[16][17][18][19][20][21]

Four states in the modern era, Nebraska in 2008, New York and Kansas in 2004, and Massachusetts in 1984, had their statutes ruled unconstitutional by state courts. The death rows of New York and Massachusetts were disestablished. Of the four states, only Nebraska has performed executions since the constitutionality of capital punishment was affirmed by the Supreme Court in 1976, the four states having done so last in 1997, 1963, 1965, and 1947, respectively. In New York and Massachusetts, attempts to restore the death penalty were unsuccessful,[22][23] while Kansas successfully appealed State v. Kleypas to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Kansas Supreme Court decision which declared the state's death penalty statute unconstitutional, and death sentences continue to be sought. New York had previously abolished the death penalty temporarily, in 1860.[24] Nebraska has performed three executions since 1976, all in the 1990s; its statute has been ineffective since February 8, 2008, when the method used, electrocution, was ruled unconstitutional by the Nebraska Supreme Court. The Governor, a critic of the Court's decision, has yet to give final approval to the bill, though he is highly likely to do so.[25][26][27] The only jurisdictions with constitutional death penalty statutes that have not performed an execution since 1976 are New Hampshire, Kansas, and the United States military, although all have populated death rows. Since 1976, South Dakota has executed "only" one man, but the execution was his own wish, so South Dakota can be regarded as a state with "de-facto moratorium" like Kansas and New Hampshire. However, in February 2010, bills to repeal the death penalty in Kansas and in South Dakota were rejected.

History

In 1608, the first person was sentenced to death in America. The person was hanged for spying for the Spanish government. He was living in Jamestown colony, the first British colony in America (in present day Virgina near Williamsburg). Capital punishment has been illegal in the U.S. state of Michigan since 1846, making Michigan's death penalty history unusual in contrast to many other states. Michigan was the first English-speaking government in the world to abolish the death penalty for all crimes except treason.[28][29][30]

The Espy file[31] lists 15,269 people executed in the United States and its predecessors between 1608 and 1991. 4,661 executions occurred in the U.S. in the period from 1930 to 2002 with about two-thirds of the executions occurring in the first 20 years.[32] Additionally the United States Army executed 135 soldiers between 1916 and 1999.[33][34][35]

The largest single execution in United States history was the hanging of 38 Dakota people convicted of murder and rape in the Dakota War of 1862. They were executed simultaneously on December 26, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota. A single blow from an axe cut the rope that held the large four-sided platform, and the prisoners (except for one whose rope had broken, and who consequently had to be restrung) fell to their deaths.[36] The second largest mass execution in United States history was also a hanging: the execution of 13 African American soldiers for their parts in the Houston Riot in 1917. The largest non-military public mass execution in one of the original thirteen colonies occurred in 1723 when 26 pirates were executed in Newport, Rhode Island by order of the Admiralty Court.[37]

Suspension by Supreme Court

| Jurisdiction | Executions[nb 1] | Current death row inmates[nb 2] |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | 464 | 336 |

| Virginia | 108 | 15 |

| Oklahoma | 93 | 84 |

| Florida | 69 | 398 |

| Missouri | 67 | 61 |

| Alabama | 49 | 200 |

| Georgia | 48 | 106 |

| North Carolina | 43 | 167 |

| South Carolina | 42 | 63 |

| Ohio | 41 | 168 |

| Louisiana | 28 | 85 |

| Arkansas | 27 | 42 |

| Arizona | 24 | 135 |

| Indiana | 20 | 15 |

| Delaware | 14 | 19 |

| California | 13 | 697 |

| Mississippi | 13 | 61 |

| Illinois | 12 | 15 |

| Nevada | 12 | 77 |

| Utah | 7 | 10 |

| Tennessee | 6 | 90 |

| Maryland | 5 | 5 |

| Washington | 5 | 9 |

| Nebraska | 3 | 11 |

| Pennsylvania | 3 | 222 |

| Federal govt | 3 | 59 |

| Montana | 3 | 2 |

| Kentucky | 3 | 35 |

| Oregon | 2 | 32 |

| Colorado | 1 | 3 |

| Connecticut | 1 | 10 |

| Idaho | 1 | 17 |

| New Mexico | 1 | 2[nb 3] |

| South Dakota | 1 | 3 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 1 |

| Kansas | 0 | 10 |

| New Hampshire | 0 | 1 |

| U.S. Military | 0 | 8 |

| Total[nb 4] | 1,233 | 3,256 |

| No current death penalty statute: Alaska, Hawaii, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico[nb 3], North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin, District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and U.S. Virgin Islands.

Statute ruled unconstitutional: Massachusetts[nb 5] and New York[nb 6]. Notes:

|

||

Capital punishment was suspended in the United States from 1972 through 1976 primarily as a result of the Supreme Court's decision in Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972). In this case, the court found the imposition of the death penalty in a consolidated group of cases to be unconstitutional, on the grounds of cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the eighth amendment to the United States Constitution.

In Furman, the United States Supreme Court considered a group of consolidated cases. The lead case involved an individual convicted under Georgia's death penalty statute, which featured a "unitary trial" procedure in which the jury was asked to return a verdict of guilt or innocence and, simultaneously, determine whether the defendant would be punished by death or life imprisonment.

In a five-to-four decision, the Supreme Court struck down the imposition of the death penalties in each of the consolidated cases as unconstitutional. The five justices in the majority did not produce a common opinion or rationale for their decision, however, and agreed only on a short statement announcing the result. The narrowest opinions, those of Byron White and Potter Stewart, expressed generalized concerns about the inconsistent application of the death penalty across a variety of cases but did not exclude the possibility of a constitutional death penalty law. Stewart and William O. Douglas worried explicitly about racial discrimination in enforcement of the death penalty. Thurgood Marshall and William J. Brennan, Jr. expressed the opinion that the death penalty was proscribed absolutely by the Eighth Amendment as "cruel and unusual" punishment.

Though many observers expected few, if any, states to readopt the death penalty after Furman, 37 states did in fact enact new death penalty statutes which attempted to address the concerns of White and Stewart. Some of the states responded by enacting "mandatory" death penalty statutes which prescribed a sentence of death for anyone convicted of certain forms of murder (White had hinted such a scheme would meet his constitutional concerns in his Furman opinion).

Other states adopted "bifurcated" trial and sentencing procedures, with various procedural limitations on the jury's ability to pronounce a death sentence designed to limit juror discretion. The Court clarified Furman in Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976) and Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 325 (1976), 431 U.S. 633 ( 1977), which explicitly forbade any state from punishing a specific form of murder (such as that of a police officer) with a mandatory death penalty.

Capital punishment resumed

In 1976, contemporaneously with Woodson and Roberts, the Court decided Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976) and upheld a procedure in which the trial of capital crimes was bifurcated into guilt-innocence and sentencing phases. At the first proceeding, the jury decides the defendant's guilt; if the defendant is innocent or otherwise not convicted of first-degree murder, the death penalty will not be imposed. At the second hearing, the jury determines whether certain statutory aggravating factors exist, and whether any mitigating factors exist, and, in many jurisdictions, weigh the aggravating and mitigating factors in assessing the ultimate penalty — either death or life in prison, either with or without parole.

The 1977 Coker v. Georgia decision barred the death penalty for rape, and, by implication, for any offense other than murder. The current federal kidnapping statute, however, may be exempt due to the fact that the death penalty applies if the victim expires in the perpetrator's custody, not necessarily by his hand, thus stipulating a resulting death, which was the wording of the objection. In addition, the federal government retains the death penalty for such non-murder offenses as treason, espionage and crimes under military jurisdiction; there has been no challenge to these statutes as of 2007.

Executions resumed on January 17, 1977, when Gary Gilmore went before a firing squad in Utah. But the pace was quite halting due to use of litigation tactics which involved filing repeated writs for habeas corpus, which succeeded for many in delaying their actual execution for many years. Although hundreds of individuals were sentenced to death in the U.S. during the 1970s and early 1980s, only ten people besides Gilmore (who had waived all of his appeal rights) were actually executed prior to 1984.

The United States Supreme Court, though, has placed two major restrictions on the use of the death penalty. First, the Supreme Court case of Atkins v. Virginia, decided June 20, 2002,[38] held that executions of mentally retarded criminals are "cruel and unusual punishments" prohibited by the Eighth Amendment. Generally, a person with an IQ below 70 is considered to be mentally retarded. Prior to this decision, between 1984 and 2002 forty-four mentally retarded inmates were executed.[39]

Second, in 2005 the Supreme Court's decision in Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005), abolished executions for persons under the age of 18 (the age is determined at the time of crime, not the trial date).

New Mexico repealed its death penalty statute on March 17, 2009, becoming the second state (after New Jersey) to abolish the death penalty since executions resumed in 1976. The law, signed by Governor Bill Richardson, took effect on July 1, 2009 and replaces the death penalty with a life sentence without the possibility of parole. The law, though, is not retroactive – inmates currently on New Mexico's Death Row and persons convicted of capital offenses committed before this date may still be sentenced to death under New Mexico's pre-existing death penalty statute.

Possibly in part due to expedited federal habeas corpus procedures embodied in the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, the pace of executions has picked up. Since the death penalty was reauthorized in 1976 1,210 people have been executed, almost exclusively by the states, with most occurring after 1990. Texas has accounted for over a third of modern executions (and over four times as many as Virginia, the state with the second-highest number); California has the greatest number of prisoners on death row, but has held relatively few executions. See the table for executions and death row inmates by jurisdiction.

Crimes subject to capital punishment

Crimes subject to the death penalty vary by jurisdiction. All jurisdictions that use capital punishment designate the highest grade of murder a capital crime, although most jurisdictions require aggravating circumstances. Treason is a capital offense in several jurisdictions.[40]

Other capital crimes include: the use of a weapon of mass destruction resulting in death, espionage, terrorism, certain violations of the Geneva Conventions that result in the death of one or more persons, and treason at the federal level; aggravated rape in Louisiana, Florida,[41] and Oklahoma; extortionate kidnapping in Oklahoma; aggravated kidnapping in Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky and South Carolina; aircraft hijacking in Alabama; drug trafficking resulting in a person's death in Connecticut and Florida;[42] train wrecking which leads to a person's death, and perjury which leads to a person's death in California.[40][43][44]

Additionally, the Uniform Code of Military Justice allows capital punishment for a list of offenses during wartime including: desertion, mutiny, spying, and misconduct before the enemy. In practice, no one has been executed for a crime other than murder or conspiracy to murder since James Coburn was executed for robbery in Alabama on September 4, 1964.[45]

On June 25, 2008 in Kennedy v. Louisiana, the US Supreme Court ruled against Louisiana's child rape death penalty, saying "there is a distinction between intentional first-degree murder on the one hand and nonhomicide crimes against individual persons."[46] The Court went beyond the question in the case to also rule out the death penalty for any crime against an individual (as opposed to "offenses against the state," such as treason or espionage, or crimes against humanity) "where the victim’s life was not taken."[47]

As of November 2008, there is only one person on death row facing capital punishment who has not been convicted of murder. Lindsey Thompson remains under a death sentence in Georgia for the crime of "Kidnapping With Bodily Injury." Thompson was convicted in 2006 for the Kidnapping and Bodily Injury of victim Gloria Ann Wilbur. Wilbur was kidnapped and beaten in Georgia, raped in Tennessee, and murdered in Kentucky. Thompson was never charged with the murder of Wilbur in Kentucky, but was sentenced to death by a jury in Georgia for Kidnapping with Bodily Injury.[48][49]

Several people who were executed have received posthumous pardons for their crimes. For example, slave revolt was a capital crime, and many who were executed for that reason have since been posthumously pardoned.

The last executions solely for crimes other than homicide:

| Crime | Convict | Date | State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aiding a runaway slave | Starling Carlton | 1859 | South Carolina |

| Arson | George Hughes, George Smith, and Asbury Hughes | August 1884 | Alabama |

| Burglary | Frank Bass | August 8, 1941 | Alabama |

| Criminal assault | Rudolph Wright | January 11, 1962 | California |

| Concealing the birth/death of an infant | Hannah Piggen | 1785 | Massachusetts (Middlesex County) |

| Conspiracy to Commit Murder | Five unnamed Yuki men | July 21, 1863 | California[50] |

| Counterfeiting | Thomas Davis | October 11, 1822 | Alabama |

| Desertion | Eddie Slovik | January 31, 1945 | Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, France (Firing squad).[51] |

| Espionage | Ethel and Julius Rosenberg | June 19, 1953 | New York (Federal execution) |

| Forgery | Unknown defendant | March 6, 1840 | South Carolina |

| Horse stealing (Grand Larceny) | Theodore Velenquez | January 30, 1852 | California[52] |

| Kidnapping | Billy Monk | November 21, 1960 | California |

| Piracy | Nathaniel Gordon | February 21, 1862 | New York (Federal execution) |

| Rape | Ronald Wolfe | May 8, 1964 | Missouri |

| Robbery | James Coburn | September 4, 1964 | Alabama |

| Robbery/rape/kidnapping | Caryl Chessman | May 2, 1960 | California |

| Slave revolt | Caesar, Sam, and Sanford (slaves) | October 19, 1860 | Alabama |

| Theft | Jake (slave) | December 3, 1855 | Alabama |

| Train Robbery | Black Jack Ketchum | April 26, 1901 | New Mexico Territory |

| Treason | John Conn | 1862 | Texas |

| Sodomy/buggery/bestiality | Joseph Ross | December 20, 1785 | Pennsylvania (Westmoreland County) |

| Witchcraft | Manuel | June 15, 1779 | Illinois (present-day) |

The legal process

The legal administration of the death penalty in the United States is complex. Typically, it involves four critical steps: (1) Sentencing, (2) Direct Review, (3) State Collateral Review, and (4) Federal Habeas Corpus. Recently, a narrow and final fifth level of process—(5) the Section 1983 Challenge—has become increasingly important.[53] (Clemency or Pardon, through which the Governor or President of the jurisdiction can unilaterally reduce or abrogate a death sentence, is an executive rather than judicial process.[54])

Direct review

If a defendant is sentenced to death at the trial level, the case then goes into a direct review.[55] The direct review process is a typical legal appeal. An appellate court examines the record of evidence presented in the trial court and the law that the lower court applied and decides whether the decision was legally sound or not.[56] Direct review of a capital sentencing hearing will result in one of three outcomes. If the appellate court finds that no significant legal errors occurred in the capital sentencing hearing, the appellate court will affirm the judgment, or let the sentence stand.[55] If the appellate court finds that significant legal errors did occur, then it will reverse the judgment, or nullify the sentence and order a new capital sentencing hearing.[57] Lastly, if the appellate court finds that no reasonable juror could find the defendant eligible for the death penalty, a rarity, then it will order the defendant acquitted, or not guilty, of the crime for which he/she was given the death penalty, and order him sentenced to the next most severe punishment for which the offense is eligible.[57] About 60% survive the process of direct review intact.[58]

State collateral review

At times when a death sentence is affirmed on direct review, it is considered final. Yet, supplemental methods to attack the judgment, though less familiar than a typical appeal, do remain. These supplemental remedies are considered collateral review, that is, an avenue for upsetting judgments that have become otherwise final.[59] Where the prisoner received his death sentence in a state-level trial, as is usually the case, the first step in collateral review is State Collateral Review. (If the case is a federal death penalty case, it proceeds immediately from direct review to federal habeas corpus.) Although all states have some type of collateral review, the process varies widely from state to state.[60] Generally, the purpose of these collateral proceedings is to permit the prisoner to challenge his sentence on grounds that could not have been raised reasonably at trial or on direct review.[61] Most often these are claims, such as ineffective assistance of counsel, which require the court to consider new evidence outside the original trial record, something courts may not do in an ordinary appeal. State Collateral Review, though an important step in that it helps define the scope of subsequent review through Federal Habeas Corpus, is rarely successful in and of itself. Only around 6% of death sentences are overturned on State Collateral Review.[62]

Federal habeas corpus

After a death sentence is affirmed in State Collateral Review, the prisoner may file for Federal Habeas Corpus (from the Latin for "produce the body"; cf. habeas corpus), which is a unique type of lawsuit that can be brought in federal courts. Federal habeas corpus is a species of collateral review, and it is the only way that state prisoners may attack a death sentence in federal court (other than petitions for certiorari to the United States Supreme Court after both direct review and state collateral review). The scope of federal habeas corpus is governed by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which restricted significantly its previous scope. The purpose of Federal habeas corpus is to ensure that state courts, through the process of direct review and State Collateral Review, have done at least a reasonable job in protecting the prisoner's Federal Constitutional Rights. Prisoners may also use Federal habeas corpus suits to bring forth new evidence that they are innocent of the crime, though to be a valid defense at this late stage in the process, evidence of innocence must be truly compelling.[63]

Review through federal habeas corpus is narrow in theory, but it is important in practice. According to Eric Freedman, 21% of death penalty cases are reversed through federal habeas corpus.[62]

James Lieberman, a professor of law at the Columbia law school, stated in 1996 that his study found that when habeas corpus petitions in death penalty cases were traced from conviction to completion of the case that there was "a 40 percent success rate in all capital cases from 1978 to 1995."[64] Similarly, a study by Ronald Tabek in a law review article puts the success rate in habeas corpus cases involving death row inmates even higher, finding that between "1976 and 1991, approximately 47% of the habeas petitions filed by death row inmates were granted."[65] The different numbers are largely definitional, rather than substantive. Freedam's statistics looks at the percentage of all death penalty cases reversed, while the others look only at cases not reversed prior to habeas corpus review.

A similar process is available for prisoners sentenced to death by the judgment of a federal court.[66]

Section 1983 contested

Under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, a state prisoner is ordinarily only allowed one suit for habeas corpus in federal court. If the federal courts refuse to issue a writ of habeas corpus, an execution date may be set. In recent times, however, prisoners have postponed execution through a final round of federal litigation using the Civil Rights Act of 1871 — codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1983 — which allows people to bring lawsuits against state actors to protect their federal constitutional and statutory rights.

Traditionally, Section 1983 was of limited use for a state prisoner under sentence of death because the Supreme Court has held that habeas corpus, not Section 1983, is the only vehicle by which a state prisoner can challenge his judgment of death.[67] In the 2006 Hill v. McDonough case, however, the United States Supreme Court approved the use of Section 1983 as a vehicle for challenging a state's method of execution as cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment. The theory is that a prisoner bringing such a challenge is not attacking directly his judgment of death, but rather the means that the judgment will be carried out. Therefore, the Supreme Court held in the Hill case, a prisoner can use Section 1983 rather than habeas corpus to bring the lawsuit. Yet, as Clarence Hill's own case shows, lower federal courts have often refused to hear suits challenging methods of execution on the ground that the prisoner brought the claim too late and only for the purposes of delay. Further, the Court's decision in Baze v. Rees, upholding a lethal-injection method used by many states, has drastically narrowed the opportunity for relief through § 1983.

Mitigating factor

The United States Supreme Court in Penry v. Lynaugh and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Bigby v. Dretke have been clear in their decisions that jury instructions in death penalty cases that do not ask about mitigating factors regarding the defendant's mental health violate the defendant's Eighth Amendment rights, saying that the jury is to be instructed to consider mitigating factors when answering unrelated questions. This ruling suggests that specific explanations to the jury are necessary to weigh mitigating factors.

Methods

Color key: State uses only this method State uses this method primarily but has secondary methods State has never used this method

Various methods have been used in the history of the American colonies and the United States but only five methods are currently used. Historically, burning, pressing, breaking on wheel, and bludgeoning were used for a small number of executions, while hanging was the most common method. The last person burned at the stake was a black slave in South Carolina August 1825.[68] The last person to be hanged in chains was a murderer named John Marshall in West Virginia April 4, 1913. Although beheading was a legal method in Utah from 1851 to 1888, it was never used.[69]

The last use of the firing squad between 1608 and the moratorium on judicial executions between 1967 and 1977 was when Utah shot James Rodgers March 30, 1960. The last use of the gallows between 1608 and the moratorium was when Kansas hanged George York June 22, 1965. The last use of the electric chair between the first electrocution August 6, 1890 and the moratorium was when Oklahoma electrocuted James French August 10, 1966. The last use of the gas chamber between the first gassing February 8, 1924 and the moratorium was when Colorado gassed Luis Monge June 2, 1967.

The moratorium ended January 17, 1977 with the shooting of Gary Gilmore by firing squad in Utah. The first use of the electric chair after the moratorium was the electrocution of John Spenkelink in Florida May 25, 1979. The first use of the gas chamber after the moratorium was the gassing of Jesse Bishop in Nevada October 22, 1979. The first use of the gallows after the moratorium was the hanging of Westley Allan Dodd in Washington January 5, 1993. December 7, 1982 is also an important day in the history of capital punishment in the United States; Charles Brooks, Jr., put to death in Texas, was the first person executed by lethal injection.

Until the 21st century, electrocution and gassing were the most prevalent methods of execution in the United States. The electrocutions of John Evans and Horace Franklin Douglas, Jr. in Alabama, Jesse Tafero, Pedro Medina and Allen Lee Davis in Florida, Alpha Otis Stephens in Georgia, William E. Vandiver in Indiana, Frank J. Coppola, Wilbert Lee Evans and Derick Lynn Peterson in Virginia and the gassings of Jimmy Lee Gray in Mississippi and Donald Eugene Harding in Arizona were horribly botched and are often cited by opponents of capital punishment.

Currently lethal injection is the method used or allowed in all of the 37 states which allow the death penalty. Nebraska required electrocution, but in 2008 the state supreme court ruled the method is unconstitutional. In mid-2009 Nebraska officially changed its method of execution to lethal injection.[70][71][72] Other states also allow electricity, firing squads, hanging and lethal gas. From 1976 to August 10, 2010 there were 1,222 executions, of which 1,048 were by lethal injection, 157 by electrocution, 11 by gas chamber, 3 by hanging, and 3 by firing squad.[73]

The method of execution of federal prisoners for offenses under the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 is that of the state in which the conviction took place. If the state has no death penalty, the judge must choose a state with the death penalty for carrying out the execution. For offenses under the 1988 Drug Kingpin Law, the method of executions is lethal injection. Federal Correctional Complex, Terre Haute is currently the home of the only death chamber for federal death penalty recipients in the United States, where they receive lethal injection.

The use of lethal injection has become standard. From June 2000 to July 20, 2009, only 6 out of 387 executions have been by a different method. The last execution by any other method:

| Method | Date | State | Convict |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrocution | March 18, 2010 | Virginia | Paul Powell |

| Shooting | June 18, 2010 | Utah | Ronald Lee Gardner |

| Lethal gas | March 3, 1999 | Arizona | Walter LaGrand[74] |

| Hanging | January 25, 1996 | Delaware | William Bailey |

Montana, until recently, was one of four states allowing the execution of a death sentence by hanging:

The punishment of death must be inflicted by administration of a continuous, intravenous injection of a lethal quantity of an ultra-fast-acting barbiturate in combination with a chemical paralytic agent until a coroner or deputy coroner pronounces that the defendant is dead.—Montana Code Annotated 46-19-103 (3).[75]

The remaining three states that allow hanging[76] are Delaware and New Hampshire, who allow it at the decision of the Corrections officials,[77] and Washington, at the decision of the prisoner.[78]

Electrocution was the preferred method of execution during the 20th century. They developed a special nickname: Old Sparky (however, Alabama's electric chair became known as the "Yellow Mama" due to its unique color). Some, particularly in Florida, were noted for malfunctions, which caused discussion of their cruelty and resulted in a shift to lethal injection as the preferred method of execution. Although lethal injection dominates as a method of execution, some states allow prisoners on death row choose the method used to execute them.

Regardless of the method, an hour or two before the execution, the condemned person is offered religious services, and a last meal. Executions are carried out in private with only invited persons able to view the proceedings.

Ages of condemned prisoners

.png)

.png)

.png)

Since 1642 (in the 13 colonies, the United States under the Articles of Confederation, and the current United States) an estimated 364 juvenile offenders have been put to death by states and the federal government. The earliest known execution of a prisoner for crimes committed as a juvenile was Thomas Graunger in 1642. Twenty-two of the executions occurred after 1976, in seven states. Due to the slow process of appeals, it was highly unusual for a condemned person to be under 18 at the time of execution. The youngest person to be executed in the 20th century was George Stinney, electrocuted in South Carolina at the age of 14, June 16, 1944. The last execution of a juvenile may have been Leonard Shockley, who died in the Maryland gas chamber April 10, 1959, at the age of 17. No one has been under age 19 at time of execution since at least 1964.[79][80] Since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976, 22 people have been executed for crimes committed under the age of 18. 21 were 17 at the time of the crime. The last person to be executed for a crime committed as a juvenile was Scott Hain April 3, 2003 in Oklahoma.[81]

Before 2005, of the 38 U.S. states that allow capital punishment:

- 19 states and the federal government had set a minimum age of 18,

- Five states had set a minimum age of 17, and

- 14 states had explicitly set a minimum age of 16, or were subject to the Supreme Court's imposition of that minimum.

16 was held to be the minimum permissible age in the 1988 Supreme Court of the United States decision of Thompson v. Oklahoma. The Supreme Court, considering the case Roper v. Simmons, in March 2005, found execution of juvenile offenders unconstitutional by a 5–4 margin, effectively raising the minimum permissible age to 18. State laws have not been updated to conform with this decision. Under the US system, unconstitutional laws do not need to be repealed, but are instead held to be unenforceable. (See also List of juvenile offenders executed in the United States)

Distribution of sentences

Within the context of the overall murder rate, the death penalty cannot be said to be widely or routinely used in the United States; in recent years the average has been about one execution for about every 700 murders committed, or 1 execution for about every 325 murder convictions.

Among genders, only 0.9% of those executed since 1976 have been women.

Among those sentenced

It is noted that the death penalty is sought and applied more often in some jurisdictions, not only between states but within states. A 2004 Cornell University study showed that while 2.5% of murderers convicted nationwide were sentenced to the death penalty, in Nevada 6% were given the death penalty.[82] Texas gave 2% of murderers the death sentence, less than the national average. Texas, however, executed 40% of those sentenced, which was about four times higher than the national average. California had executed only 1% of those sentenced.

Among races

African Americans made up 41% of death row inmates while making up only 12% of the general population. (They have made up 34% of those actually executed since 1976.)[83] However, that number is lower than that of prison inmates, which is 47%[84] U.S. Department of Justice statistics show that African-Americans constituted 48 percent of adults charged with homicide, but only 41 percent of those sentenced of death. Once arrested for murder, African-Americans are less likely to receive a capital sentence than are White Americans.[85]

Academic studies indicate that the single greatest predictor of whether a death sentence is given, however, is not the race of the defendant, but the race of the victim. According to a 2003 Amnesty International report, Africans and Europeans were the victims of murder in almost equal numbers, yet 80% of the people executed since 1977 were convicted of murders involving white victims.[83] But, others say intra-racial murders, most likely between persons who know one another are circumstances often viewed as inappropriate for the death penalty. Because those sentenced to death often don't know their victims (e.g., killing during rape or robbery), their victim is likely to be European.[85]

Among convicts, half of the ten inmates on Connecticut's death row, all races included, have been condemned for the murders of minorities, and five of the 37 inmates executed in South Carolina were Caucasian men convicted of murdering Blacks. In October 2000, a study[86] of La Griffe du Lion, an anonymous scholar accused on Internet forums of "scientifical fraud"[87], based on the difference between homicide ratio among races and death row inmates' races, concludes that distribution of death sentences is biased in Southern states against Non-Hispanic Whites, where most of the executions take place, biased against Blacks in Pennsylvania, and neutral in the other states of Midwest and West.

Public vs. private execution

The last public execution in America was that of Rainey Bethea in Owensboro, Kentucky, on August 14, 1936. It was the last death sentence in the nation at which the general public was permitted to attend without any legally-imposed restrictions. "Public execution" is a legal phrase, defined by the laws of various states, and carried out pursuant to a court order. Similar to "public record" or "public meeting," it means that anyone who wants to attend the execution may do so.

Around 1890, a political movement developed in the United States to mandate private executions. Several states enacted laws which required executions to be conducted within a "wall" or "enclosure" to "exclude public view." For example, in 1919, the Missouri legislature adopted a statute (L.1919, p. 781) which required, "the sentence of death should be executed within the county jail, if convenient, and otherwise within an enclosure near the jail." The Missouri law permitted the local sheriff to distribute passes to individuals (usually local citizens) who he believed should witness the hanging, but the sheriffs—for various reasons—sometimes denied passes to individuals who wanted to watch. Missouri executions conducted after 1919 were not "public" because they were conducted behind closed walls, and the general public was not permitted to attend.

Present-day statutes from across the nation use the same words and phrases, requiring modern executions to take place within a wall or enclosure to exclude public view. Connecticut (CGSA 54-100) requires death sentences to be conducted in an "enclosure" which "shall be so constructed as to exclude public view." Kentucky (KRS 431.220) and Missouri (VAMS 546.730) statutes contain substantially identical language. New Mexico's statute (NMSA 31-14-12) requires executions be conducted in a "room or place enclosed from public view." A dormant Massachusetts law (MGLA. 279 § 60) requires executions to take place "within an enclosure or building." North Carolina (NCGSA § 15-188) requires death sentences to be executed "within the walls" of the penitentiary, as do Oklahoma (22 Okl.St.Ann. § 1015) and Montana (MCA 46-19-103). Ohio (RC § 2949.22) requires that "The enclosure shall exclude public view." Similarly, Tennessee (TCA § 40-23-116) requires "an enclosure" for "strict seclusion and privacy." Federal law (18 U.S.C.A. § 3596 and 28 CFR 26.3) specifically limits the witnesses to be present at an execution.

Today, there are always witnesses to executions—sometimes numerous witnesses, but it is the law, not the number of witnesses present, which determines whether the execution is "public."

All of the executions which have taken place since the 1936 hanging of Bethea in Owensboro have been conducted within a wall or enclosure. For example, Fred Adams was legally hanged in Kennett, Missouri, on April 2, 1937, within a 10-foot (3 m) wooden stockade. Roscoe "Red" Jackson was hanged within a stockade in Galena, Missouri, on May 26, 1937. Two Kentucky hangings were conducted after Galena in which numerous persons were present within a wooden stockade, that of John "Peter" Montjoy in Covington, Kentucky on December 17, 1937, and that of Harold Van Venison in Covington on June 3, 1938. An estimated 400 witnesses were present for the hanging of Lee Simpson in Ryegate, Montana, on December 30, 1939. The execution of Timothy McVeigh on June 11, 2001, was witnessed by some 300 people (some by closed circuit television).

Clemency and commutations

The largest number of clemencies was granted in January 2003 in Illinois, when outgoing Governor George Ryan, who had already imposed a moratorium on executions, pardoned four death-row inmates and commuted the sentences of the remaining 167 to life in prison without the possibility of parole.[88]

Previous post-Furman mass clemencies took place in 1986 in New Mexico, when Governor Toney Anaya commuted all death sentences because of his personal opposition to the death penalty. However, two of these inmates escaped shortly afterwards, one kidnapping a family of four in California. In 1991 outgoing Ohio Governor Dick Celeste commuted the sentences of eight prisoners among them all four women on the state's death row. And during his two terms (1979–1987) as Florida Governor, Bob Graham, although a strong death penalty supporter who had overseen the first post-Furman involuntary execution as well as 15 others, agreed to commute the sentences of six people on grounds of "possible innocence" or "disproportionality."

Controversy over use of death penalty

Various groups oppose or support capital punishment. Amnesty International and some religions oppose capital punishment on moral grounds, while the Innocence Project works to free wrongly convicted prisoners, including death row inmates, based on newly available DNA tests. Other groups, such as the Southern Baptists, law enforcement organizations, and some victims' rights groups support capital punishment.

Opinion polls consistently show that a majority of the American public supports the death penalty. An October 2008 Gallup poll had 64% of respondents in "favor of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder". In the same Gallup poll, when life imprisonment without parole was given as an option as a punishment for murder, 56% supported the death penalty and 39% supported life imprisonment, with 5% offering no opinion.[89] Elections have sometimes turned on the issue; in 1986, three justices were removed from the Supreme Court of California by the electorate (including Chief Justice Rose Bird) partly because of their opposition to the death penalty.

Religious groups are widely split on the issue of capital punishment,[90] generally with more conservative groups more likely to support it and more liberal groups more likely to oppose it. The Fiqh Council of North America, a group of highly influential Muslim scholars in the United States, has issued a fatwa calling for a moratorium on capital punishment in the United States until various preconditions in the legal system are met.[8]

The debate over the death penalty centers around four issues: whether it is morally correct to kill; whether the death penalty serves as a deterrent; whether the penalty is being applied fairly across racial, social, and economic classes; and whether the irrevocability of the penalty is justified considering possible new evidence or future revelations of improper conduct by the state. It is also claimed that the financial costs of a complete death penalty case exceed the total costs of a lifetime of incarceration.[91] Between 1976 and 2003, fewer than 2% of death row prisoners were exonerated (that is, cleared of all alleged crimes), while others had their sentences reduced for other reasons. This amounted to 112 prisoners released.

Suicide on death row

The suicide rate of death row inmates was found by Lester and Tartaro to be 113 per 100,000 for the period 1976–1999. This is about ten times the rate of suicide in the United States as a whole and about six times the rate of suicide in the general U.S. prison population.[92]

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico instituted a four-year moratorium on the use of the death penalty in 1917. The last execution took place in 1927 and the Puerto Rican legislature abolished the death penalty in 1929.[93]

Puerto Rico's constitution expressly forbids capital punishment, setting it apart from all US states and territories other than Michigan, which also has a constitutional prohibition (eleven other states and the District of Columbia have abolished capital punishment through statutory law); however, capital punishment is still applicable to offenses committed in Puerto Rico, if they fall under the jurisdiction of the federal government.

Moratoria and de-facto moratoria

Since the reinstatement of the death penalty, Kansas and New Hampshire have not used it yet, and South Dakota has executed only one man, but the execution was his own wish. Therefore, these three states can be regarded as having "de-facto moratoria." However, in February 2010, bills to abolish the death penalty in Kansas and in South Dakota were rejected. Since the death penalty was reinstated in Illinois in 1977, 12 men have been executed. During that same period, 13 men were freed from death row.[94] This finding prompted the outgoing governor of Illinois, Republican George H. Ryan, who had previously ordered a moratorium on executions by the state, to commute all death penalties in his state in January 2003.[95] When Democrat Rod Blagojevich was elected governor in 2002, one of his first acts was an attempt to revoke some of Ryan's commutations.[96]

In addition to Ryan's moratorium, Governor Parris N. Glendening (D) halted executions in the state of Maryland by executive order on May 9, 2002, but the subsequent governor, Robert Ehrlich (R), resumed executions in 2004. However, on December 19, 2006, the Maryland Court of Appeals ruled that state executions would be suspended until the manual that spells out the protocol for lethal injections is reviewed by a legislative panel. The state's Department of Corrections had adopted the manual without having a public hearing or submitting it before a committee. Legislative review of the protocol is required before approval under state law.

In December 2005, the New Jersey State Senate passed a one-year moratorium on executions by the state.[97] The measure was passed by the legislature on January 10, 2006. Governor Richard J. Codey signed the measure into law on January 12.[98] New Jersey is the first state to pass such a moratorium legislatively, rather than by executive order. Although New Jersey reinstated the death penalty in 1982, the state has not executed anyone since 1963. On December 17, 2007, with the signing of an abolition bill by Governor Jon Corzine, New Jersey became the 14th state without a death penalty at a time when its use is declining in most of the 36 states—plus the federal government and U.S. military—that retain it, but the first state to recently abolish it by legislative action rather than by judicial decision. As a result, all eight inmates on death row had their sentences commuted to life in prison. This was upsetting to some, as the list included Jesse Timmendequas, whose rape and murder of his 7-year-old neighbor, Megan Kanka, led to the creation of Megan's Law, and many awaited his execution.[99]

In New York, the New York State Court of Appeals ruled that the state's death penalty statute was unconstitutional in June 2004, in the case of People v. LaValle.

In Florida, Governor Jeb Bush suspended all executions on December 15, 2006 after a botched execution required a second injection of the lethal chemicals. The moratorium was lifted on July 18, 2007 by Governor Charlie Crist,[100] and on November 1, 2007, the Florida Supreme Court unanimously upheld the state's lethal injection procedures.[101]

In North Carolina, a de facto moratorium is in place following a decision by the state's medical board that physicians cannot participate in executions, which is a requirement under state and federal law.

In California, U.S. District Judge Jeremy Fogel imposed a moratorium on the death penalty in the state of California on December 15, 2006, ruling that the implementation used in California was unconstitutional but that it could be fixed.[102]

In Missouri, U.S. District Judge Fernando J. Gaitan, Jr. of the United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri in Kansas City suspended the state's death penalty on June 26, 2006, after lengthy hearings on the matter. Judge Gaitan reasoned that the state's lethal injection protocol did not satisfy the Eighth Amendment because (1) the written procedures for implementing lethal injections were too vague, and (2) the state had no qualified anesthesiologist to perform lethal injections. Jay Nixon, the Missouri Attorney General, promptly appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in St. Louis. On June 4, 2007, a panel of the Eighth Circuit reversed the District Court's decision. The death row inmate in question, Michael Taylor, will seek an en banc hearing before the entire Eighth Circuit and, failing that, will seek a writ of certiorari in the Supreme Court of the United States.[103] The Eighth Circuit case is number 06-3651, Taylor v. Crawford.

In Nebraska, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled, on February 8, 2008, that the use of the electric chair is unconstitutional — specifically, that its use conflicts with the Nebraska State Constitution. As electrocution was the sole legally-authorized method of execution in Nebraska, the state had what technically amounts to no legally-authorized death penalty,[104] until the introduction of lethal injection in that state in May 2009.[105]

After the Supreme Court of the United States agreed to hear the case Baze v. Rees many states had slowed or halted executions as lawyers for death-row prisoners argued that states should not carry out death sentences using a method that may be ruled unconstitutional. While executions had come to an apparent stop until Baze was examined by the court, this was not the intent, according to Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who stated on October 16, 2007 that stopping all executions by that method was not the high court's intention when it agreed to hear Baze. Just because the justices agreed to take on the case, Scalia said, does not necessarily mean that a moratorium should ensue.[106]

On April 16, 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court decided in Baze that the current method of execution by lethal injection, by use of a three-drug 'cocktail', is constitutionally permissible even though an alternative method such as a massive overdose of some other drug could be used and might be less painful or less uncomfortable for the condemned. As a result of the court's decision, some states that had instituted stays or moratoria subsequently announced a resumption of executions.

On November 25, 2009, the Kentucky Supreme Court Wednesday placed a moratorium on executions until it adopts regulations for carrying out the penalty by lethal injection.[107]

New developments

- In October 2009, the American Law Institute voted to disavow the framework for capital punishment that it had created in 1962, as part of the Model Penal Code, "in light of the current intractable institutional and structural obstacles to ensuring a minimally adequate system for administering capital punishment." A study commissioned by the institute had said that experience had proved that the goal of individualized decisions about who should be executed and the goal of systemic fairness for minorities and others could not be reconciled.[108]

- Colorado might abolish death penalty in the near future.[109]

- February 2010: In Alaska, a bill to reinstate the death penalty is being discussed, but its sponsors think there will be not enough support. In Kansas and South Dakota, bills to abolish the death penalty were rejected.

- 2004: Utah made lethal injection the only form of capital punishment. However those already on death row were grandfathered on the type of execution they had chose at sentencing. At the time of the change in the law there were still three inmates on Utah's death row that had selected firing squad.

See also

- List of U.S. Supreme Court decisions on capital punishment

- List of exonerated death row inmates

- Capital punishment by the United States federal government

- Opposition to capital punishment in the United States

External resources

Anti-death penalty

- National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

- Death Penalty Information Center (opposition not stated)

- Texas Moratorium Network

- The Innocence Project

- Truth in Justice

- Amnesty International USA campaign to abolish the death penalty

- Campaign to end the Death Penalty

- Against the Death Penalty — Religious Organization

- Orthodox Peace Fellowship

- Death Penalty Focus

- Fight the death penalty

- Anti-Death Penalty Information: includes a monthly watchlist of upcoming executions and death penalty statistics for the United States.

- German Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty: includes detailed information on the death penalty in the USA

- National Lawyers Guild

Pro-death penalty

- http://www.off2dr.com

- Pro Death Penalty.com

- Josh Marquis, the justice system, politics and the media

- Clark County, IN Prosecutor's Page on capital punishment

- In Favor of Capital Punishment - Quotes supporting Capital Punishment by Saqib Ali

- The Ultimate Punishment - A professor defends the death penalty

- Is man a moral agent? - Ethics of capital punishment

- A defense of the death penalty

- Death Penalty Information - News, arguments and links

- Criminal Justice Legal Foundation Articles on the death penalty, and deterrence

Question of racial bias

- Reporting a study finding no intentional racial bias - CNN Law Center archives

More information

- "U.S. Army Corrections System: Procedures for Military Executions" - Department of the Army

- About.com's Pros & Cons of the Death Penalty and Capital Punishment (Liberal Viewpoint)

- Last Meals on Death Row

- The documentary Procedure 769, witness to an execution DocsOnline focuses on the people who witness an execution, specifically that of Robert Alton Harris who murdered two boys in 1978.

References

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ "Facts About the Death Penalty", http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/FactSheet.pdf, Death Penalty Information Center, April 1, 2008

- ↑ execution since 1976

- ↑ Executions Slowed in 2008, But Numbers May Increase in Coming Year

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ "Executions in the United States in 2009", http://deathpenaltyinfo.org/executions-united-states-2009, Death Penalty Information Center

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ American Justice Volume 1

- ↑ Letter - Cost of the Death Penalty

- ↑ STUDY: COST SAVINGS FROM REPEAL OF DEATH PENALTY MAY BE ELUSIVE

- ↑ Green, Melissa S. (July 20, 2001; revised September 21, 2001). "A History of the Death Penalty in Alaska". University of Alaska Anchorage. http://justice.uaa.alaska.edu/death/alaska/history.html. Retrieved July 15, 2010. "Alaska as a state has never had a death penalty. However, in Alaska's territorial days, eight men were executed under civil authority between 1900 and 1957. Other persons in Alaska were executed extrajudicially in the late 19th century under so-called "miner's laws." There is currently no easily available information on executions that may have taken place under military authority in Alaska."

- ↑ Hugo Adam Bedau (1980). "The 1964 Death Penalty Referendum in Oregon". http://cad.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/26/4/528. Retrieved December 23, 2009. "In Oregon, six times in this century, the death penalty has confronted the voters at the polls. In 1964, in an event unparalleled in our history, the death penalty was abolished in public referendum by a wide margin."

- ↑ Richburg, Keith B. (December 14, 2007). "N.J. Approves Abolition of Death Penalty; Corzine to Sign". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/12/13/AR2007121301302.html. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ (English) Maria Medina, « Governor OK with Astorga capital case »

- ↑ "New Mexico governor bans death penalty". Agence France-Presse. March 18, 2009. Archived from the original on December 23, 2009. http://www.webcitation.org/5mEkMGy25. Retrieved 2009-12-23. "LOS ANGELES (AFP) — New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson made his state the 15th in the nation to outlaw capital punishment when he signed a law abolishing the death penalty, his office said."

- ↑ No serious chance of repeal in those states that are actually using the death penalty

- ↑ AG Brown says he'll follow law on death penalty

- ↑ lawmakers-cite-economic-crisis-effort-ban-death-penalty

- ↑ death penalty is not likely to end soon in US

- ↑ Death penalty repeal unlikely says anti-death penalty activist

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ Powell, Michael (2005-04-13). "In N.Y., Lawmakers Vote Not to Reinstate Capital Punishment". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A47871-2005Apr12.html. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Ring, Dan (2007-11-08). "House rejects death penalty". The Republican. http://www.masslive.com/springfield/republican/index.ssf?/base/news-2/119451180886550.xml&coll=1. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ "WHEN NEW YORK HAD NO DEATH PENALTY; Punishment for Murder Under Law of 1860 Curiously Limited to a Year in Prison.". The New York Times. 1912-01-21. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9F0CE7D8123AE633A25752C2A9679C946396D6CF. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- ↑ "Neb. lethal-injection plan advances". KTIV / Associated Press. 2009-12-08. Archived from the original on 2009-12-23. http://www.webcitation.org/5mEk0s8DS. Retrieved 2009-12-23. "LINCOLN, Neb. (AP) — A proposed lethal-injection protocol in Nebraska has been submitted to Attorney General Jon Bruning for approval. Last week, the state Department of Correctional Services signed off on the three-drug cocktail and the process of administering it to death-row inmates. The department devised the proposed protocol and did not make any changes to the proposal after some raised concerns about it, including that it doesn't clearly specify how workers should be trained to administer the drugs. If Bruning approves the proposal, it will go to Gov. Dave Heineman for final approval."

- ↑ "The year in review, a look back at 2009 Part 2". KTIV. http://www.ktiv.com/Global/story.asp?S=11717401. Retrieved 2009-12-23. "When the Nebraska Unicameral gaveled into session, the state was without a method to carry out capital punishment. The Nebraska Supreme Court ruled the electric chair unconstitutional. Norfolk State Senator Mike Flood introduced a bill that would make lethal injection legal. The bill had full support of Governor Dave Heineman."

- ↑ "Ohio executes inmate with 1-drug lethal injection". Associated Press. December 8, 2009. Archived from the original on December 23, 2009. http://www.webcitation.org/5mEkZTdUI. Retrieved December 23, 2009. "All 36 death penalty states use lethal injection, and 35 rely on the three-drug method. Nebraska, which recently adopted injection over electrocution, has proposed the three-drug method but hasn't finalized it."

- ↑ Information on States Without the Death Penalty

- ↑ History of the Death Penalty - Faith in Action - Working to Abolish the Death Penalty

- ↑ See Caitlin pp. 420-422

- ↑ Espy file

- ↑ Department of Justice of the United States of America

- ↑ The U.S. Military Death Penalty

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_A._Bennett

- ↑ Executions in the Military

- ↑ "The Dakota Conflict Trials of 1862". http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/dakota/dakota.html. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ↑ John T. Brennan, Ghosts of Newport: Spirits, Scoundrels, Legends and Lore (The History Press, 2007), pg. 15 [6](accessed on Google Books on July 20, 2009)

- ↑ "DARYL RENARD ATKINS, PETITIONER v. VIRGINIA". June 20, 2002. http://supct.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/00-8452.ZO.html. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

- ↑ http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/list-defendants-mental-retardation-executed-united-states

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Death Penalty for Offenses Other Than Murder http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/article.php?&did=2347, Death Penalty Information Center, 2008, accessed January 28, 2008

- ↑ Florida styles what would be common law rape as "sexual battery." Sexual batteries which could receive the death penalty if Kennedy v. Louisiana were overturned are found in The 2009 Florida Statutes § 794.011(2)(a) & (8)(c), available at http://www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm

- ↑ See The 2009 Florida Statutes § 782.04(1)(a)(3), available at http://www.leg.state.fl.us/Statutes/index.cfm

- ↑ Legislative Information

- ↑ Communications Office of California.

- ↑ The ESPY file for James Coburn

- ↑ "Child rapists can't be executed, Supreme Court rules", http://www.cnn.com/2008/CRIME/06/25/scotus.child.rape/index.html?eref=rss_topstories, Bill Mears, CNN, June 25, 2008

- ↑ Supreme Court Rejects Death Penalty for Child Rape

- ↑ http://www.lawskills.com/case/ga/id/1652/

- ↑ http://www.dcor.state.ga.us/GDC/OffenderQuery/jsp/OffQryRedirector.jsp Click "Offender Search" at the top. Search for "Sears, Demarcus" in the name search.

- ↑ Berry, Irene; O'Hare, Sheila and Silva, Jesse (2006). Legal Executions in California: A Comprehensive Registry, 1851-2005. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, p. 61.

- ↑ The Sad Story of Private Eddie Slovik

- ↑ Berry, Irene; O'Hare, Sheila and Silva, Jesse (2006). Legal Executions in California: A Comprehensive Registry, 1851-2005. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, p. 10.

- ↑ See, e.g., Hill v. McDonough.

- ↑ See generally Separation of Powers.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 See, e.g., 18 U.S.C. § 3595. ("In a case in which a sentence of death is imposed, the sentence shall be subject to review by the court of appeals upon appeal by the defendant."

- ↑ See generally Appeal.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Poland v. Arizona, 476 U.S. 147 152-54 (1986).

- ↑ Eric M. Freedman, "Giarratano is a Scarecrow: The Right to Counsel in State Postconviction Proceedings, Legalize Drugs" 91 Cornell L. Rev. 1079, 1097 (2006).

- ↑ Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288, 306 (1989).

- ↑ LaFave, Israel, & King, 6 Crim. Proc. § 28.11(b) (2d ed. 2007).

- ↑ LaFave, Israel, & King, 6 Crim. Proc. § 28.11(a) (2d ed. 2007).

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Eric M. Freedman, "Giarratano is a Scarecrow: The Right to Counsel in State Postconviction Proceedings," 91 Cornell L. Rev. 1079, 1097 (2006).

- ↑ House v. Bell, 126 S. Ct. 2064 (2006)

- ↑ "Habeas Corpus Studies". The New York Times. April 1, 1996. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05E0DB1039F932A35757C0A960958260. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ frontline: the execution: readings: the new speed-up in habeas corpus appeals

- ↑ see 28 U.S.C. § 2255.

- ↑ Heck v. Humphrey, 512 U.S. 477 (1994).

- ↑ The Espy File

- ↑ MSU website page on Death Penalty information

- ↑ Nebraska court bans the electric chair

- ↑ NY Times article: Electrocution Is Banned in Last State to Rely on It

- ↑ Nebraska Supreme Court opinion

- ↑ Death Penalty Info Fact Sheet.

- ↑ NAACPLDF DRUSA, Spring 2006.

- ↑ Montanta Code Annotated 46-19-103 (3), as amended Sec. 6, Ch. 491, L. 1999, found at Montana State Official website. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ State-by-state methods of execution. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ New Hampshire Laws, TITLE LXII: Criminal Code, Chapter 630: Homicide, Section 630:5, Procedure in Capital Murder. – Clause XIV. From statutes 1974, 34:10. 1977, 440:2. 1986, 82:1. 1990, 199:3, eff. Jan. 1, 1991. Found at General Court of New Hamshire State Official website. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Revised Code of Washington, RCW 10.95.180 (Title 10, Chapter 10.95, Section 10.95.180) "Death penalty — How executed." Found at Washington State Legislature Official website. Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ↑ Best Web

- ↑ Juvenile News and Developments - Previous Years

- ↑ Execution of Juveniles in the U.S. and other Countries

- ↑ "Explaining Death Row's Population and Racial Composition," The Journal of Empirical Legal Studies John Blume, Theodore Eisenberg and Martin Wells, March 2004, cited in Cornell Press release

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 United States of America: Death by discrimination - the continuing role of race in capital cases. | Amnesty International

- ↑ Death Penalty in Black and White (1999 figures).

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 [7])

- ↑ THE COLOR OF DEATH ROW

- ↑ http://newsgroups.derkeiler.com/Archive/Rec/rec.music.classical.guitar/2008-06/msg00072.html

- ↑ Illinois Death Row Inmates Granted Commutation by Governor George Ryan on January 12, 2003

- ↑ ClarkProsecutor

- ↑ ReligiousTolerance

- ↑ Experts Agree: Death Penalty Not A Deterrent To Violent Crime, http://news.ufl.edu/1997/01/15/death1/, January 15, 1997, accessed September 27, 2007

- ↑ "Suicide on death row", David Lester and Christine Tartaro, Journal of Forensic Sciences, ISSN 0022-1198, 2002, vol. 47, no5, pp. 1108-1111

- ↑ http://www.initiative-gegen-die-todesstrafe.de/en/death-penalty-world-wide/usa/puerto-rico-a-special-case.html - 'Puerto Rico - A Special Case' by the German Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty

- ↑ Oprah

- ↑ Suburban Chicago News

- ↑ Press Enterprise

- ↑ Justice Policy

- ↑ New Jersey ADP

- ↑ MSNBC News Services (2007-12-13). "N.J. Legislature votes to abolish death penalty". http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22249232/. Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- ↑ JURIST - Paper Chase: Florida governor lifts temporary ban on executions

- ↑ JURIST - Paper Chase: Florida Supreme Court upholds state lethal injection procedure

- ↑ Judge says executions unconstitutional

- ↑ Court restores Missouri executions The Kansas City Star, June 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Nebraska Supreme Court says electrocution unconstitutional", Omaha World-Hearld (online edition), February 8, 2008.

- ↑ Volentine, Jason (2009-05-28). "Nebraska Changes Execution Method to Lethal Injection". KOLN. http://www.kolnkgin.com/political/headlines/46424547.html. Retrieved 2009-05-30.

- ↑ Gramlich, John (2007-10-18). "Lethal injection moratorium inches closer". Stateline.org. http://www.stateline.org/live/details/story?contentId=249581. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ http://www.kentucky.com/news/local/story/1035605.html

- ↑ Adam Lipak (January 4, 2010). "Group Gives Up Death Penalty Work". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/05/us/05bar.html.

- ↑ John Tomasic (November 9, 2009). "Colorado budget woes may force an end to death penalty". Colorado Independent. http://coloradoindependent.com/41746/colorado-budget-woes-may-force-an-end-to-death-penalty.

Further reading

- Banner, Stuart (2002). The Death Penalty: An American History. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00751-4.

- Delfino, Michelangelo and Mary E. Day. (2007). Death Penalty USA 2005 - 2006 MoBeta Publishing, Tampa, Florida. ISBN 978-0-9725141-2-5; and Death Penalty USA 2003 - 2004 (2008). MoBeta Publishing, Tampa, Florida. ISBN 978-0972514132.

- Dow, David R., Dow, Mark (eds.) (2002). Machinery of Death: The Reality of America's Death Penalty Regime. Routledge, New York. ISBN 0-415-93266-1 (cloth), ISBN 0-415-93267-X (paperback) (this book provides critical perspectives on the death penalty; it contains a foreword by Christopher Hitchens)

- Megivern, James J. (1997), The Death Penalty: An Historical and Theological Survey. Paulist Press, New York. ISBN 0-8091-0487-3

- Osler, Mark William (2009). Jesus on Death Row: The Trial of Jesus and American Capital Punishment. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0687647569

- Prejean, Helen (1993). Dead Man Walking. Random House. ISBN 0-679-75131-9 (paperback)

(Describes the case of death row convict Elmo Patrick Sonnier, while also giving a general overview of issues connected to the Death Penalty.)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||